The Current #14

Opportunities for the Next Generation of Neobanks

by Hunter WorlandOct 23, 2025

Introduction

Banks have always mirrored their time in purpose, model, and product. The world’s first bank that is still operational, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, reflected Franciscan tradition in Renaissance Italy, financing harvests and trade through reputation-based credit rooted in communal duty. In the Gilded Age, the House of Morgan channeled capital to railroads, oil, and steel through its private syndicate. Its model mirrored a time of scale, industry, and the handshake deal. Or, on the 19th-century American frontier, “wildcat” banks printed their own notes in an economy starved of currency; speculative institutions for a speculative society.

The more recent wave of neobanks are no exception. They compressed traditional banking into the decade’s preferred interface: the mobile app. Simultaneously, viral digital distribution met a post-recessionary (and post-bailout) cultural demand for democratization.

Drawing on new survey data, this piece explores what a modern bank, built with today’s tech like stablecoins, programmable money, and AI, might look like if designed for the greatest financial challenges retail banking customers face. The throughline behind how tech can support a new generation of iconic companies is how new banking platforms can leverage context, more specifically the ability to design around the individual rather than the average.

Part I - Definitions

First, we should define the core concepts.

Context

Context is what allows a product to truly understand its user, particularly their circumstances, constraints, and intent at a given moment. It combines quantitative data (think income, credit score, transaction history, cash-flow timing) with qualitative signals (think life events and aspirations, communication style, spending psychology, social graph). In practice, context turns a static profile into a living model of a person’s financial reality. Context is the antidote to genericism in that it enables financial products to adapt to individuals rather than forcing individuals to adapt to a set of products.

Bank

And what is a bank? The average consumer might imagine two kinds. The first, traditional: branches, tellers, a bank charter, and an integrated stack of deposits, credit, and payments, typically credit cards and mortgages attached. The second is digital: a neobank that rebuilt mostly that same product set inside a mobile app rather than a branch.

That conception is fading, driven by structural shifts like:

Banking-as-a-service: Compliance, settlement, licensing have become services that non-banks can effectively rent through APIs. The consumer-facing brand is often disconnected from the regulated entity holding the charter through BaaS providers. As a result, “banking” now happens wherever intent meets money like at checkout, inside a crypto wallet, or even within a message thread

Tokenization and stablecoins: Stablecoins also blur the boundary because they allow non-banks to deliver the core functions people expect from a bank like storing value, earning yield, and making instant payments, without holding deposits or maintaining a charter. They effectively restructure the deposit model, shifting yield generation from bank balance sheets to market instruments held in reserve. Under the GENIUS framework, issuers can’t pay interest directly, but they can share reserve income with distributors who surface it as “rewards” which creates savings-like value through partnerships rather than deposit-taking.2

The blurriness is part of the opportunity because the less rigid the definition of a bank, the greater the opportunity to redesign it.

Part II - Path to genericism

Genericism, the counterpart of context, is the convergence of products, interfaces, and decision systems. Consumers see genericism in how most banking apps seem to look and feel alike: a checking and savings tabs, a credit card offer, similar rates on similar products, an offers marketplace, similar customer service scripts. Even the neobanks that once promised reinvention typically operate within the same visual and economic grammar. This genericism is neither inherently good nor bad as much as it just reflects structural forces like:

Neobanking value proposition: In neobanking’s ramp up years in the late 2000s through 2010s, simply digitizing core functions created massive value. The act of digitization alone expanded access and lowered costs, so there was little reason to narrow the market by developing a more contextual product

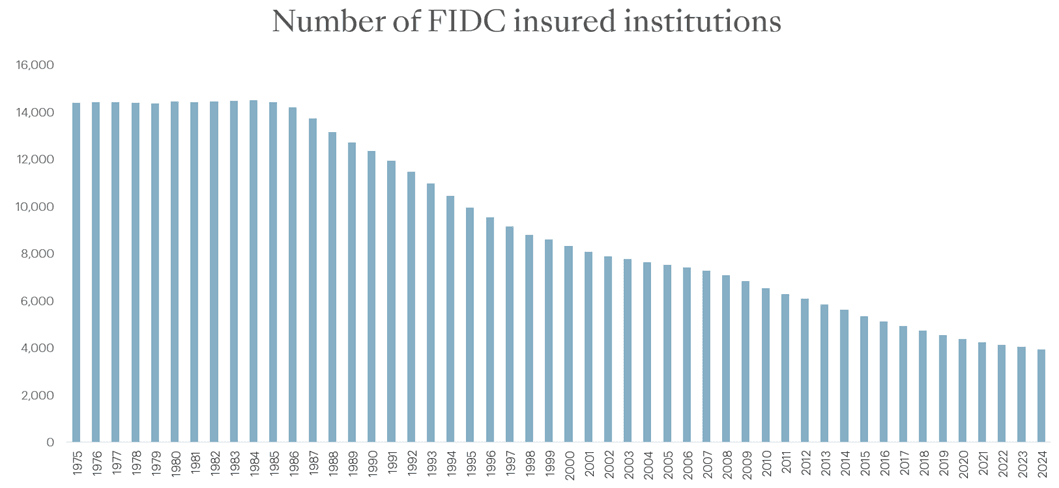

Consolidation: Mergers and post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) regulation concentrated assets into a handful of megabanks. As community banks and credit unions disappeared, so did many local relationships that once enabled more contextual lending and underwriting

Regulatory uniformity: Post-GFC frameworks such as Basel III and Dodd-Frank steered large banks toward common risk and capital standards. Higher capital ratios, liquidity rules, and stress-testing requirements made experimentation in pricing or structure expensive and complex

Limits of scale and data: Retail banking’s economics favor uniformity. Most financial products generate too little margin to justify true customization, so banks rely on standardized templates that can scale. The focus has shifted from designing products around individuals to using data to fit individuals into pre-set products

Technological standardization: Most incumbents and neobanks operate on the same core processors, card networks, and vendor infrastructure which can constrain foundational differentiation

The logic of bigness: As banking consolidates, financial services products consequently have to serve an even larger scale. The sheer size and diversity of their customer bases incentivize offering broad, easily marketed value propositions (e.g., travel or dining rewards for credit cards) even if it flattens nuance

Part III - Pain points

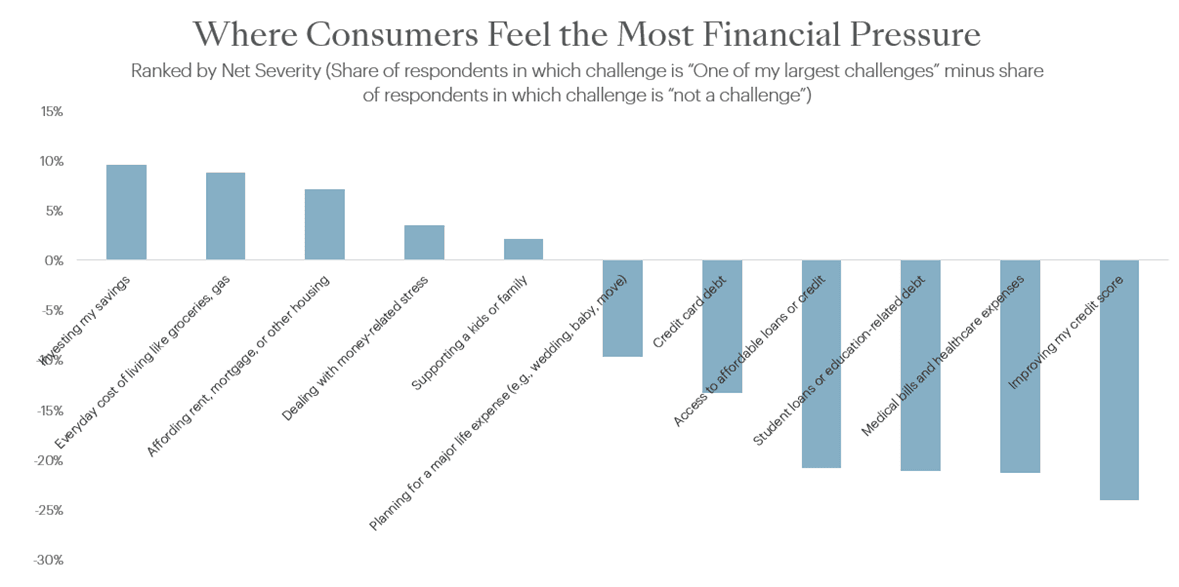

The best opportunities in consumer finance start with the biggest pain points. I asked our panel of consumers ages 18-64, living in the United States to identify their largest financial challenges, both qualitatively and through a structured list of eleven categories. Each challenge was scored by taking the share of respondents who said it was one of their largest challenges less those who said it was not a challenge, excluding those who answered in the middle (“a moderate challenge”) or said it was not relevant (for example, student debt). The highest-scoring pain points were savings, affordability, and stress.

Most qualitative responses are generally along the same lines, like: “inflation is way out of control and i'm just not making enough to keep up with it”; “everything is getting more expensive and my paycheck isn’t keeping up.”

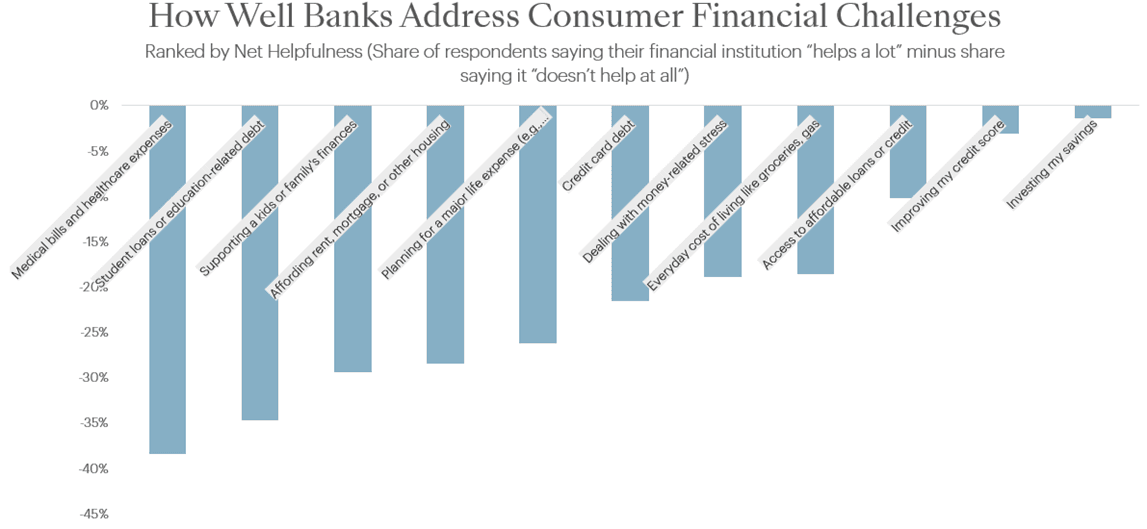

When asked how well their financial institutions help them address these challenges, the results were underwhelming. I used a similar scoring method: those who said their bank helps a lot less those who said it does not help at all, excluding middle responses (“helps a little”) and “not relevant.” Every category produced a negative score. In other words, for every major financial challenge, more respondents felt their bank does not help at all than those who felt it helps meaningfully. Worst is largely affordability across medical, educational, housing, and everyday personal and family expenses.

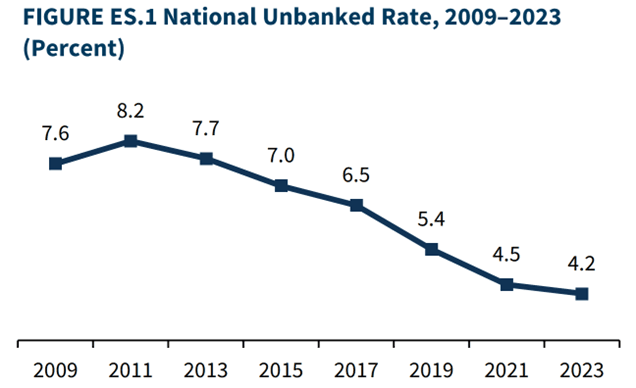

These scores should be put in context with the innovation of the last generation, which largely succeeded in expanding inclusion i.e., lowering barriers to open an account, move money, and invest. Just as a benchmark, mobile banking helped drive the U.S. unbanked rate to historic lows:

But accessibility is only the first step because it does not yet fundamentally solve outcomes, which sets the stage for the next frontier.

Part IV - Five hypotheses on how to meet the moment

So, how can technology solve the foundational problems consumers face like affordability, savings, and stress, building on the foundations of neobanking? Roughly, three shifts now expand what’s possible in fintech:

Programmability through blockchain enables money to move and behave according to pre-set rules, automating functions that once required back-office staff

New payment rails make transactions instant and near-free

AI collapses human bandwidth and cost constraints, letting systems reason over context, personalize services, and automate judgment at scale

Together, these tools create a foundation for a more adaptive, contextual financial stack. Below are five ideas on how this could reshape the next generation of financial products.

1. N-of-1 finance: Most financial products are still mass-produced. Outside private banking, products assume an average customer because building anything tailored has never been economical. AI starts to change that by making customization scalable, in particular:

Understanding context: not just the customer’s intent for a product, but, through natural language, how that intent fits within a much richer picture of their financial life than a FICO score

Co-design the product: instead of a one-way offer to accept or reject, the institution and customer can iterate together in real time, adjusting levers like collateral, term length, or repayment structure through a conversational interface

The north star is a financial system that can design and deliver a product for a single user where the marginal cost of personalization approaches zero. Beyond better outcomes for the core mass-market demographic, customization at scale should both reach new segments that were previously too complex or costly to underwrite and expand lifetime value by lifting product attach rates and retention.

2.Compressing costs, passing back savings: AI and programmable money can remove significant costs that make credit expensive like underwriting, reconciliation, collections and compliance. For example:

Smarter capital allocation: Banks of course set aside large static reserves to cover potential loan losses. With real-time performance data and programmable reserves held on-chain, capital buffers could automatically loosen idle cash when defaults are low and tighten when risk rises. That dynamism would trap less capital and lower funding costs

Automated compliance and reconciliation: Smart contracts can verify transactions, confirm counterparty data, and reconcile payments which eliminate redundant human checks and third-party intermediaries. Smart contracts can complete what used to take days and manual effort in seconds (and with an audit trail)

Contextual collections: Instead of relying on call centers and scripted outreach, lenders can use data to understand a borrower’s real ability to pay and respond accordingly, while adjusting tone, timing, and repayment structure to fit each case. This should not only compress a large non-interest expense (the average call-center interaction costs as much as $12 per interaction)6 but also improve credit outcomes. Proactive, contextual outreach can reduce delinquency roll rates, translating to lower charge-off ratios and provision expenses. For secured loans, programmable contracts can even automate parts of that process, triggering partial repayments or margin calls when conditions change

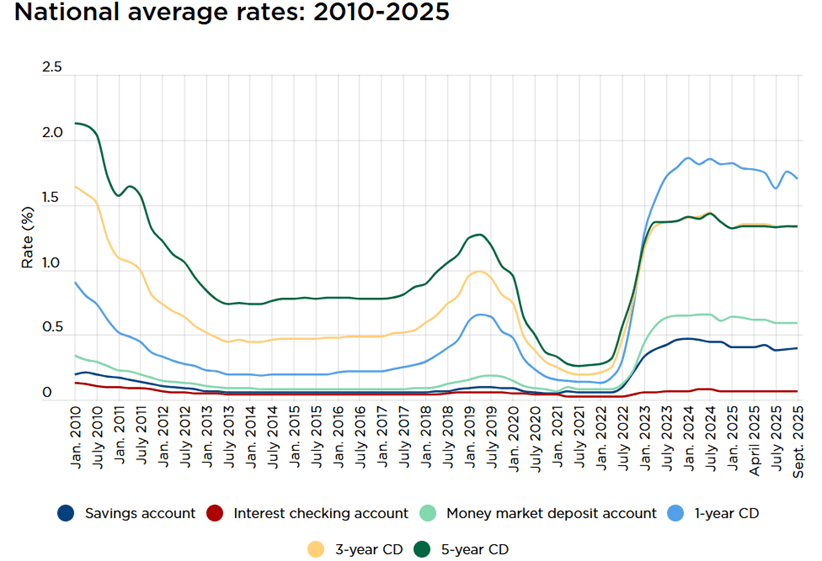

3. Higher automated yields: Most savings accounts still pay under 0.5%, even as Treasury yields have risen several points in recent years. 7 The spread between what banks earn and what savers receive remains wide. While consumers have always been able to move idle cash into higher-yield vehicles, it requires manual effort, minimum balances, and some degree of sophistication.

Tokenization and DeFi infrastructure make it possible to connect retail deposits to a broader range of yield sources such as tokenized Treasuries, repo markets, and short-term credit pools. These models disintermediate the traditional deposit–lending spread by connecting savers directly to the same yield sources banks invest in, rather than routing returns through balance-sheet intermediaries. Over time, savings could evolve from a static balance to a continuously optimized portfolio where context determines how each dollar is allocated. Owning the customer’s savings use case confers both the right to win and the context to originate higher-value products like credit or insurance.

4. New interfaces: Financial stress ranked among the top challenges in our survey, yet few respondents said they felt comfortable discussing money with their bank. When asked to describe a dream financial assistant, respondents consistently used words like patient, clear, trustworthy, and nonjudgmental. One said they wanted someone who would “help me plan without making me feel dumb.” Another described “someone who listens, explains things in simple terms, and actually cares if I’m doing better.”

This gap is partly emotional but also structural since most banking interfaces are relatively transactional. Natural-language interfaces allows for continuous dialogue through text or voice, supported by memory and context. An assistant could recall prior conversations, recognize stress or uncertainty, and tailor responses accordingly. As one respondent said, “I just want someone to tell me what’s happening and why, not make me feel like I should already know.”

The result is a relationship layer (akin to a community banking relationship of yesteryear) that restores continuity, reduces stress, and helps users make sense of their finances through more natural interfaces.

5. Reward mechanics: Today’s reward systems seem misaligned with real financial stress. Take credit cards. Many of the issuer’s largest programs like Chase Sapphire, Chase Freedom, Capital One Venture Rewards or direct co-brands with partners like Delta, Marriott, or Hilton focus either on aspirational rewards like travel and dining or widely accepted brand partnerships like Amazon Prime. These rewards are designed for scale, not relevance, persisting because they generically appeal to a wide swath of users (lean affluent), less that they solve foundational problems. A few ideas on how startups can leverage existing models and technology to redesign reward mechanics and capture large consumer transaction value from incumbents:

Merchant-funded affordability: Merchants already fund incentives to drive conversion. Buy Now, Pay Later platforms proved this model in that they primarily use merchant discount rates to finance zero-interest credit for some consumers (only 26% of Klarna’s revenue in Q2 for instance was interest income9). The same logic of re-allocating existing marketing and interchange economics toward outcomes that matter more (companies like PayZen are doing this in healthcare, for instance)

Personalized, programmable rewards: Most reward systems are built for the median (lean affluent) customer which incents travel points, dining perks, and brand tie-ins that have little to do with real financial stress. They often reflect the lowest common denominator for a mass customer base rather than a meaningful incentive structure. Programmable money and AI make it possible to rebuild that logic. Because money can now carry rules and context, rewards can be linked directly to a broader set of transactional behavior and incentives that can enable more precise, contextual rewards. At the same time, programmability allows banks to build flexible merchant networks without large in-house partnership teams. That value for retail consumers should ultimately confer high transaction retention and share of wallet.

As ever, the only constant in change. Reach out to continue the conversation at hworland@nea.com

Sources

Image: “Wildcat Banknote,” from History of Iowa. From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the Twentieth Century, Vol. 1 (1903)

U.S. Congress, Guaranteed and Enforceable Non-Interest-bearing Stablecoin Uniform Standards Act of 2024 (GENIUS Act), H.R. 4766, 118th Cong. (2024)

DragonfruitNo7222. “What Happened to Car Colours?” Reddit, r/CarsAustralia, posted April 2024. (image)

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), “Statistics on Depository Institutions (SDI),” data retrieved October 2025. (chart image)

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), “2023 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households,” Figure 1, released October 2024.

[1] Goodcall. (2024, February 21). How much does a call center cost? A full cost breakdown. Retrieved from https://www.goodcall.com/bpo/cost-breakdown

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2025). National Rates and Rate Caps: Weekly Update, September 2025. Retrieved from https://www.fdic.gov/resources/bankers/national-rates/

Ibid

Klarna Group plc. press release Klarna grows Q2 revenue to $823m, reports continued operating profitability . (August 14, 2025)

Disclaimer

These consumer surveys were conducted among a representative sample of 150+ adults living in the United States, ages 18 - 64. The surveys were fielded using the Pollfish platform during August and October 2025. Pollfish partners directly with app developers; the developer defines an appropriate and specific non-cash incentive in exchange for completed surveys that benefit real consumers but doesn’t motivate them to become career panelists. Please note that as with all survey research, there is a potential for sampling error and other forms of bias. Results should be interpreted as an indication of sentiment among the target population rather than an exact measure.

The information provided in this blog post is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended to be investment advice, or recommendation, or as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy an interest in any fund or investment vehicle managed by NEA or any other NEA entity. New Enterprise Associates (NEA) is a registered investment adviser with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). However, nothing in this post should be interpreted to suggest that the SEC has endorsed or approved the contents of this post. NEA has no obligation to update, modify, or amend the contents of this post nor to notify readers in the event that any information, opinion, forecast or estimate changes or subsequently becomes inaccurate or outdated. In addition, certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources and has not been independently verified by NEA. Any statements made by founders, investors, portfolio companies, or others in the post or on other third-party websites referencing this post are their own, and are not intended to be an endorsement of the investment advisory services offered by NEA.

NEA makes no assurance that investment results obtained historically can be obtained in the future, or that any investments managed by NEA will be profitable. To the extent the content in this post discusses hypotheticals, projections, or forecasts to illustrate a view, such views may not have been verified or adopted by NEA, nor has NEA tested the validity of the assumptions that underlie such opinions. Readers of the information contained herein should consult their own legal, tax, and financial advisers because the contents are not intended by NEA to be used as part of the investment decision making process related to any investment managed by NEA.